#BlackGirlMagic: More than a Hashtag

We’ve heard the phrase, “personal is political,” but how often do we reflect on how politics and the media play a role in our personal experiences? Today, I did just that.

It wasn’t until I reflected on how much I’ve evolved as a black woman, that I understood the true impact the #BlackGirlMagic concept and movement has left on me. #BlackGirlMagic became popularized by CaShawn Thompson in 2013. Although it started as a social media phenomenon, I internalized the messages and images of #BlackGirlMagic for a lifetime.

Starting in 2013, black women all over the world were posting inspirational photos of themselves and their accomplishments tagged with “#BlackGirlMagic.” Whether academic, professional or cosmetic, women were showing pride in their blackness and uniqueness.

Courtesy of Huffington Post

That year, my first year of college, I made the decision to stop chemically straightening my hair. I was tired of processing my hair with relaxers just for it to become brittle and break off. Like me, more black women were transitioning back to their natural hair or doing the “big chop,” where they shaved off all of their chemically straightened hair. So I thought, what better time than now? With my decision came internal push-back. Whether I had realized it at the time or not, I had internalized the idea that straight, tidy hair was beautiful. After all, I had lived the majority of my life with relaxed hair before that point.

This idea, that my natural curly hair was ugly is called “internalized racism”, which is “the personal conscious or subconscious acceptance of the dominant society’s racist views, stereotypes and biases of one’s ethnic group” (TAARM). I had subconsciously convinced myself that the hair that grew naturally out of my head was not normal. It was challenging at first to feel beautiful and feminine when I began wearing my hair in a way that felt foreign to me. I went from getting my hair relaxed before special events to look “pretty” to making the conscious decision to no longer get relaxers, which to me (at the time) meant making the decision to not be “pretty” anymore (at least not in the European idea of beauty).

With the help of the #BlackGirlMagic movement, the internalized racism that I held onto began to shed like onion layers. Women all over, posted photos of themselves with curls and kinks framing their face like art work. Over time, I began to internalize a new idea: that I was indeed “magical” and that black girls like myself had something that was unique and special to us, whether it was our hair, skin, features or determination — it was something only we shared.

I didn’t know how to wear my hair naturally and didn’t know where to begin when it came to trying to style it, but I knew I wasn’t alone. Using Youtube videos and blog sites for natural women, I began to explore the wonders of having black natural hair. Soon, I began to love it. I wondered how I spent my life lathering chemical infused cream onto my scalp just so it could fall straight.

In no time, the #BlackGirlMagic movement had spread like a virus. Mainstream publications, celebrities and music artists began using the phrase. Clicking the hashtag on Instagram was like gaining access to a network of natural girls all over the world. Since then, I have never been the same. The #BlackGirlMagic movement has expanded into something greater. It created empowerment among black women for years to come. The movement made us feel special, so we internalized that we are.

Courtesy of Pierre Jean-Louis.

In addition to transitioning from relaxed hair to natural hair, the #BlackGirlMagic movement helped me to take pride in my blackness. Before the popularization of this movement along with the many others that were introduced in the last couple years (#BlackLivesMatter, #ICantBreathe, etc.) I, for the most part, lived with a colorblind mentality. The idea of being racially colorblind as defined by Monnica T. Williams is, “the racial ideology that posits the best way to end discrimination is by treating individuals as equally as possible, without regard to race, culture, or ethnicity,” (Psychology Today).

During the years of the #BlackGirlMagic movement, I learned how thinking racially colorblind was problematic. Brushing black issues under the rug no longer sufficed for the woman I was becoming. Seeing the world without color only ignored the issues that affected the black community instead of changing them. My silence during times of black oppression only added fuel to the fire instead of putting it out.

It was October 2016, when I was at my sorority house rolling tissue paper for our styrofoam display to be in the LSU Homecoming parade. Nearly 50 girls were gathered in the chapter room where we all worked on the styrofoam Mike the Tiger.

Sitting next to me was one of my sorority sisters who I was familiar with, Grayson. Grayson and I began having small talk with the girls around us. We talked about ourselves, life and of course Beyoncé. Beyoncé performed at the super bowl that year, sparking controversy over the pro-black messages she sent through her attire and overall performance.

Courtesy of @mstinalawson of Instagram

Grayson brought up the performance, saying how annoyed she was that Beyoncé chose that moment of all moments to make a political statement. My heart beat heavily. I knew why Beyoncé chose the super bowl to make her statement. I thought to myself, what better time than the super bowl, the sole broadcast where the majority of the U.S. is watching to send everyone a message about how black lives matter?

Being one of the only five black women in my sorority, I knew it was important to speak up. If I chose to remain “colorblind,” so would the rest of the women in my organization. Hesitantly, I asked Grayson, “If Beyoncé didn’t do it at the super bowl, when else would she be able to speak to all of America on black lives? Everyone’s eyes were fixed on their T.V.s during halftime, clearly you were watching, so she got what she wanted. She got people talking about the message she wanted to convey. She strategically chose that moment.”

While Grayson didn’t have much to say after my response, I gave myself a mental pat on the back. Never before had I spoken about black lives or black issues while surrounded by all of my white sorority sisters. That moment was important to me because I knew I had removed the racial colorblind veil I had lived with my whole life. I chose to speak up knowing it would make not only myself but my sisters uncomfortable. But I knew that moment wasn’t about keeping everyone in the room comfortable, but about keeping everyone in the room informed.

In addition to helping me battle internalized racism and colorblindness, the #BlackGirlMagic movement helped me identify the cultural assimilation I practiced throughout my childhood. Cultural assimilation is, “when members of one cultural group adopt the language, practices and beliefs of another group, often losing aspects of their traditional culture in the process,” (Reference.com).

Looking back, I am able to laugh at how much I wanted to remove my blackness, but as a young girl being black felt inescapable. Growing up in Colorado Springs, CO, an area highly populated by Mexican immigrants, I wanted the privilege of having long black hair, caramel (sometimes white) skin and being bilingual like my hispanic friends. To my peers, I was “too tall,” “too black,” and my hair was, “too short.” I made efforts to make myself more “Mexican,” by frequently practicing Spanish, learning all of the popular reggaeton songs and music artists, supporting Mexican gangs and cliques and making sure I didn’t stay out in the sun too long so my skin wouldn’t get too dark.

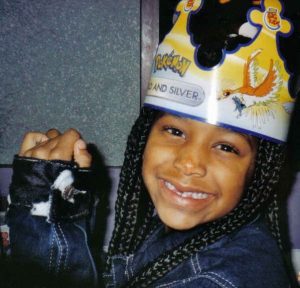

I begged my mom not to braid my hair because my peers called my box braids “snakes” and “shoelaces,” but she did anyway. I wanted to escape the color of my skin for years, but when the #BlackGirlMagic movement became popularized it was hard for me not to embrace my curls, brown skin and African heritage.

Me (Cynthea Corfah) with box braids in elementary school.

Through the movement, I developed my own sense of belonging among the the black female community and felt closer than ever to my African and black roots. The #BlackGirlMagic concept and movement was more than a hashtag. The #BlackGirlMagic movement opened my eyes to see beauty in blackness, girlhood and speaking out. Whether the hashtag loses popularity or not, the message will forever live in me.