Blue is the Warmest Color, and Sexuality is Complicated

2013’s award winning Blue is the Warmest Color was one of the most controversial and highly praised films of that season. In it, high school student Adèle begins a relationship with the older art student Emma. The film follows Adèle’s sexual awakening, and the highs and lows of first love through their relationship over roughly ten years. Blue has been panned by many viewers for issues with the male gaze and voyeurism, as well as potentially over-the-top sex scenes, but also articulately recognized for victories like the “banalisation of homosexuality” and its general film mastery. Its controversy, even among the gay and lesbian community, fascinates me. It is still a prime subject for analysis of its and the media’s treatment of lesbians, women, and female sexuality.

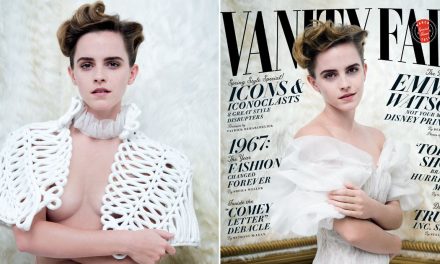

First, the most widely discussed attribute of the film: the infamous sex scene. Rated NC-17, Blue featured one particularly polarizing scene between the lead actresses, involving an abundance of sexual positions and the use of a natural camera style that made many viewers feel… uncomfortable, to say the least. The scene is nearly seven minutes long, and features an “Olympic” list of sexual positions, which many critics (both professional and amateur) found unrealistic and typical of the male gaze. The male gaze, in this case, is felt very strongly; director Abdellatif Kechiche’s “desire” for the female body was routinely described as palpable by viewers. Julie Maroh, who wrote the comic book that Blue is based on, stated in a blog post that she felt the sex scenes were somewhat predicated on another scene, in which several characters commiserate about the mystery and awesomeness of the female orgasm (especially in comparison to the male orgasm). This fetishization of lesbian sexuality is unfortunate, but as many viewers pointed out: all the sex scenes only make up a few minutes of a three hour movie. Additionally, one gay woman said that she found the sex “more real than a lot of sex [she’s] ever seen” on screen, and others have voiced similar opinions. The sex scenes were certainly unusual on the mainstream and festival film circuits, but the quality and effect of them is certainly debated.

This scene’s particular grasp and controversy goes deeper, though – it has been pointed out that of the major film reviews that specifically addressed it, only three of eighteen were written by women. Though we can’t and shouldn’t speculate on those writers’ sexuality, it seems that lesbians have not often been asked about such a famous lesbian film and scene. This lack of representation and relative exclusion from the dialogue about issues and characters that they may identify with is perhaps a partial result of the lack of women in film criticism, but also another symptom of male gaze and heteronormativity (in this case, indicating the default opinions that are being given are from [presumed] heterosexual males).

Regardless of the status or intention of the sex scenes, Blue is ultimately a film about a relationship’s blissful start, rocky middle, and tragic end. The film was almost universally praised for its portrayal of nearly boring, average parts of any relationship: conversations that don’t have much in terms of content, but seem to buzz with the electricity of newfound attraction. This is borderline revolutionary in a film regarding a same-sex female relationship – the plot actually involves very little drama as a result the main characters’ orientations. They are just women, and they just happen to love each other. Genuinely. It’s refreshing, and serves as one of seemingly few examples of lesbians in popular media that don’t end up beaten, raped, murdered, or rejected by family for their orientation. This, Maroh says, is the “banality of homosexuality.” Homosexual relationships are often like any straight relationship, with little drama or intrigue caused by virtue of sexual orientation alone. The portrayal of this reality is important and necessary, and fights not only heteronormativity but also the sexism within LGB representations. It is also important to note that same-sex marriage was legalized in France, the from whence Blue hails, in 2013, so the portrayal is especially timely.

Blue also features an abundance of close-up shots of quivering lips and teary eyes, especially as the film progresses into the tragic third act; Adèle and Emma’s relationship crumbles. The fragility and overall complexity of both lead actresses is explored, but Adèle, as the protagonist, is shown as a very well mapped character. In fact, the very fluidity and confusion inherent in sexuality is presented well through her – she struggles to fully accept her own relationship and status throughout the film, but this is mostly dealt with through subtext and subtle cues. In the very beginning of the movie Adèle is shown losing her virginity to her boyfriend, with little enthusiasm or apparent enjoyment. She then finds Emma and the pair fall in love. But Adèle once more sleeps with a man during the last period of her relationship with Emma; she, again, may not be particularly enthusiastic (as evidenced by her wandering eyes during the act), but she nevertheless proceeds. This is an important part of sexuality that is often ignored or not talked about: very little is black and white. Although Adèle may identify as a lesbian (though we don’t know for sure), she does sleep with men at some points in her life. This may not have been the result of actual attraction, but it does show the messiness and complexity of real adult sexual relationships.

This film’s controversial status has not died down in recent years: opinion pieces on personal blogs are still posted from time to time, and every viewer seems to have a strong opinion about at least some aspects of it. The most polarizing part of Blue is the Warmest Color is certainly its extended and graphic sex scenes, which have been interpreted in many ways by many viewers. Male gaze and fetishes of lesbian sex may be present, but some argue its realism overtakes both. In terms of the rest of the lead actresses’ relationship, a sense of normalcy and even banality are important for both representation and filmmaking purposes. Critics generally agree that the relationship’s realistic representation of highs and lows is heart wrenching, and this perspective raises the standard for future films featuring lesbian relationships.